Chris Oldwood from The OldWood Thing

[I’m sure there is something else going on here but on the off-chance someone else is also observing this and also lost at least they’ll know they’re not alone.]

We have a GitLab project pipeline that started out as a monolithic job but over the last 9 months has slowly been parallelized and now runs as over 150 jobs spread out across a cluster of 4 fairly decent [1] machines with 8 to 10 concurrent jobs per host. More recently we’ve started seeing the PowerShell Expand-Archive cmdlet failing randomly up to 5% of the time with the following error:

Remove-Item : Cannot find path {...} because it does not exist.

The line of code highlighted in the error is:

$expandedItems | % { Remove-Item $_ -Force -Recurse }

If you google this message it suggests this probably isn’t the real error but a problem with the cmdlet trying to clean-up after failing to extract the contents of the .zip file. Sadly the reason why the extraction might have failed in the first place is now lost.

Investigation

While investigating this error message I ran across two main hits – one from Stack Overflow and the other on the PowerShell GitHub project – both about hitting the classic long path problem in Windows. In our case the extracted paths, even including the build agent root, is still only 100 characters so well within the limit as the archive only has one subfolder and the filenames are short.

Also the archive is built with it’s companion cmdlet Compress-Archive so I doubt it’s an impedance mismatch in our choice of tools.

My gut reaction to anything spurious like this is that it’s the virus scanner (AV) [2]. Sadly I have no direct control over the virus scanner product choice or its configuration. In this instance the machines have Trend Micro whereas the other build agents I’ve built are VMs and have Windows Defender [3], but their load is also much lower. I managed to get the build folder excluded temporarily but that appears to have had no effect and nothing was logged in the AV to say it had blocked anything. (The “behaviour monitoring” in modern AV products often gets triggered by build tools which is annoying.)

After discounting the obvious and checking that memory exhaustion also wasn’t a factor as the memory load for the jobs is variable and the worst case loading can cause the page-file to be used, I wondered if there the problem lay with the GitLab runner cache somehow.

Corrupt Runner Cache?

To avoid downloading the .zip file artefact for every job run we utilise the GitLab runner local cache. This is effectively a .zip file of a packages folder in the project working copy that gets packed up and re-used in the other jobs on the same machine which, given our level of concurrency, means it’s constantly in use. Hence I wondered if our archive was being corrupted when the cache was being unpacked as I’ve seen embedded .zip files cause problems in the past for AV tools (even though it supposedly shouldn’t have been touching the folder). So I added a step to test our archive’s integrity before unpacking it by using 7-Zip as there doesn’t appear to be a companion cmdlet Test-Archive. I immediately saw the integrity test pass but the Expand-Archive step fail a few times so I’m pretty sure the problem is not archive corruption.

Workaround

The workaround which I’ve employed is to use 7-Zip for the unpacking step too and so far we’ve seen no errors at all but I’m left wondering why Expand-Archive was intermittently failing. Taking an extra dependency on a popular tool like 7-Zip is hardly onerous but it bumps the complexity up very slightly and needs to be accounted for in the docs / scripts.

In my 2017 post Fallibility I mentioned how I once worked with someone who was more content to accept they’d found an undocumented bug in the Windows CopyFile() function than believe there was a flaw in their code or analysis [4]. Hence I feel something as ubiquitous as Expand-Archive is unlikely to have a decompression bug and that there is some piece of the puzzle here that I’m missing. Maybe the AV is still interfering in some way that isn’t triggered by 7-Zip or the transient memory pressure caused by the heavier jobs is having an impact?

Given the low cost of the workaround (use 7-Zip instead) the time, effort and disruption needed to run further experiments to explore this problem further is sadly too high. For the time being annecdata is the best I can do.

[1] 8 /16 cores, 64 / 128 GB RAM, and NVMe based disks.

[2] I once did some Windows kernel debugging to help prove an anti-virus product update was the reason our engine processes where not terminating correctly under low memory conditions.

[3] Ideally servers shouldn’t need anti-virus tools at all but the principle of Defence in Depth suggests the minor performance impact is worth it to potentially help slow lateral movement.

[4] TL;DR: I quickly showed it was the latter at fault not the Windows API.

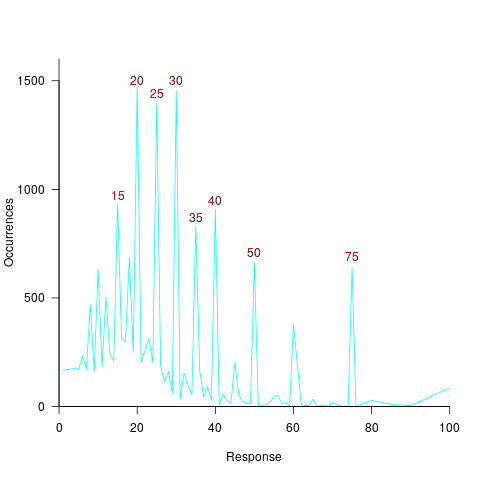

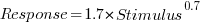

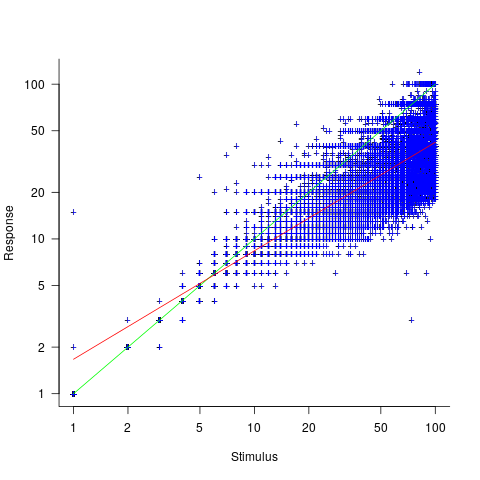

, and red line a fitted regression model having the form

, and red line a fitted regression model having the form  (which explains just over 70% of the variance;

(which explains just over 70% of the variance;

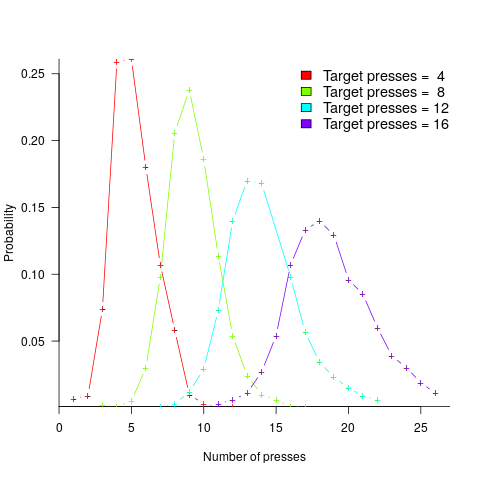

, with

, with  varying between 0.65 and 1.57; more than a factor of two difference between subjects (this model explains just under 90% of the variance). This is a smaller range than the software estimation data, but with only six subjects there was less chance of a wider variation (

varying between 0.65 and 1.57; more than a factor of two difference between subjects (this model explains just under 90% of the variance). This is a smaller range than the software estimation data, but with only six subjects there was less chance of a wider variation (