Derek Jones from The Shape of Code

Why does a particular expression appear in source code?

One reason is that the expression is the coded form of a formula from the application domain, e.g.,  .

.

Another reason is that the expression calculates an algorithm/housekeeping related address, or offset, to where a value of interest is held.

Most people (including me, many years ago) think that the majority of source code expressions relate to the application domain, in one-way or another.

Work on a compiler related optimizer, and you will soon learn the truth; most expressions are simple and calculate addresses/offsets. Optimizing compilers would not have much to do, if they only relied on expressions from the application domain (my numbers tool throws something up every now and again).

What are the characteristics of application domain expression?

I like to think of them as being complicated, but that’s because it used to be in my interest for them to be complicated (I used to work on optimizers, which have the potential to make big savings if things are complicated).

Measurements of expressions in scientific papers is needed, but who is going to be interested in measuring the characteristics of mathematical expressions appearing in papers? I’m interested, but not enough to do the work. Then, a few weeks ago I discovered: An Analysis of Mathematical Expressions Used in Practice, by Clare So; an analysis of 20,000 mathematical papers submitted to arXiv between 2000 and 2004.

The following discussion uses the measurements made for my C book, as the representative source code (I keep suggesting that detailed measurements of other languages is needed, but nobody has jumped in and made them, yet).

The table below shows percentage occurrence of operators in expressions. Minus is much more common than plus in mathematical expressions, the opposite of C source; the ‘popularity’ of the relational operators is also reversed.

Operator Mathematics C source

= 0.39 3.08

- 0.35 0.19

+ 0.24 0.38

<= 0.06 0.04

> 0.041 0.11

< 0.037 0.22

The most common single binary operator expression in mathematics is n-1 (the data counts expressions using different variable names as different expressions; yes, n is the most popular variable name, and adding up other uses does not change relative frequency by much). In C source var+int_constant is around twice as common as var-int_constant

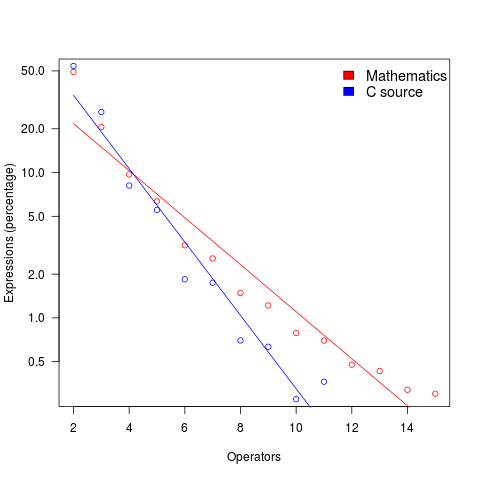

The plot below shows the percentage of expressions containing a given number of operators (I've made a big assumption about exactly what Clare So is counting; code+data). The operator count starts at two because that is where the count starts for the mathematics data. In C source, around 99% of expressions have less than two operators, so the simple case completely dominates.

For expressions containing between two and five operators, frequency of occurrence is sort of about the same in mathematics and C, with C frequency decreasing more rapidly. The data disagrees with me again...