Derek Jones from The Shape of Code

During the age of the Algorithm, developers wrote most of the code in their programs. In the age of the Ecosystem, developers make extensive use of code supplied by third-parties.

Software ecosystems are one of the primary drivers of software development.

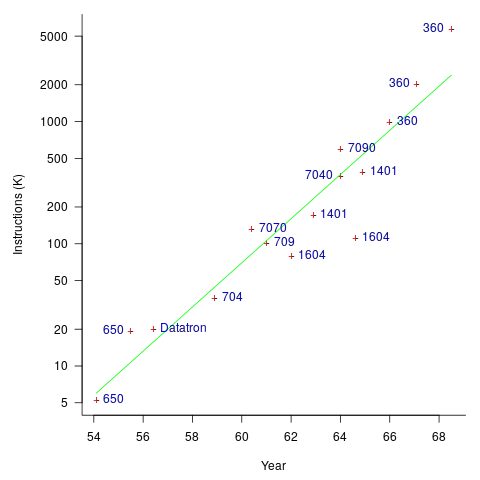

The early computers were essentially sold as bare metal, with the customer having to write all the software. Having to write all the software was expensive, time-consuming, and created a barrier to more companies using computers (i.e., it was limiting sales). The amount of software that came bundled with a new computer grew over time; the following plot (code+data) shows the amount of code (thousands of instructions) bundled with various IBM computers up to 1968 (an anti-trust case eventually prevented IBM bundling software with its computers):

Some tasks performed using computers are common to many computer users, and users soon started to meet together, to share experiences and software. SHARE, founded in 1955, was the first computer user group.

SHARE was one of several nascent ecosystems that formed at the start of the software age, another is the Association for Computing Machinery; a great source of information about the ecosystems existing at the time is COMPUTERS and AUTOMATION.

Until the introduction of the IBM System/360, manufacturers introduced new ranges of computers that were incompatible with their previous range, i.e., existing software did not work.

Compatibility with existing code became a major issue. What had gone before started to have a strong influence on what was commercially viable to do next. Software cultures had come into being and distinct ecosystems were springing up.

A platform is an ecosystem which is primarily controlled by one vendor; Microsoft Windows is the poster child for software ecosystems. Over the years Microsoft has added more and more functionality to Windows, and I don’t know enough to suggest the date when substantial Windows programs substantially depended on third-party code; certainly small apps may be mostly Windows code. The Windows GUI certainly ties developers very closely to a Windows way of doing things (I have had many people tell me that porting to a non-Windows GUI was a lot of work, but then this statement seems to be generally true of porting between different GUIs).

Does Facebook’s support for the writing of simple apps make it a platform? Bill Gates thought not: “A platform is when the economic value of everybody that uses it, exceeds the value of the company that creates it.”, which some have called the Gates line.

The rise of open source has made it viable for substantial language ecosystems to flower, or rather substantial package ecosystems, with each based around a particular language. For practical purposes, language choice is now about the quality and quantity of their ecosystem. The dedicated followers of fashion like to tell everybody about the wonders of Go or Rust (in fashion when I wrote this post), but without a substantial package ecosystem, no language stands a chance of being widely used over the long term.

Major new software ecosystems have been created on a regular basis (regular, as in several per decade), e.g., mainframes in the 1960s, minicomputers and workstation in the 1970s, microcomputers in the 1980s, the Internet in the 1990s, smart phones in the 2000s, the cloud in the 2010s.

Will a major new software ecosystem come into being in the future? Major software ecosystems tend to be hardware driven; is hardware development now basically done, or should we expect something major to come along? A major hardware change requires a major new market to conquer. The smartphone has conquered a large percentage of the world’s population; there is no larger market left to conquer. Now, it’s about filling in the gaps, i.e., lots of niche markets that are still waiting to be exploited.

Software ecosystems are created through lots of people working together, over many years, e.g., the huge number of quality Python packages. Perhaps somebody will emerge who has the skills and charisma needed to get many developers to build a new ecosystem.

Software ecosystems can disappear; I think this may be happening with Perl.

Can a date be put on the start of the age of the Ecosystem? Ideas for defining the start of the age of the Ecosystem include:

- requiring a huge effort to port programs from one ecosystem to another. It used to be very difficult to port between ecosystems because they were so different (it has always been in vendors’ interests to support unique functionality). Using this method gives an early start date,

- by the amount of code/functionality in a program derived from third-party packages. In 2018, it’s certainly possible to write a relatively short Python program containing a huge amount of functionality, all thanks to third-party packages. Was this true for any ecosystems in the 1980s, 1990s?