Allan Kelly from Allan Kelly Associates

When I deliver Agile training for teams I run an exercise called “The Extended XP Gameâ€. It is based on the old “XP Game†but over the years I’ve enhanced it and added to it. We have a lot of fun, people are laughing and they still talk about it years later. The game illustrates a lot of agile concepts: iteration, business value, velocity, learning by doing, specification by example, quality is free, risk, the role of probability and some more.

When I run the exercise I divide the trainees into several teams, usually three or four people to a team. I show them I have some tasks written on cards which they will do in a two minute iteration. They do two minutes or work, review, retrospect then do another two minutes of work – and possibly repeat a third time.

The first thing is for teams to Get Ready: I hand out the tasks and ask them to estimate, in seconds how long it will take to do each task: fold a paper airplane that will fly, inflate a balloon, deflate a balloon, roll a single six on a dice, roll a double six on two dice, find a two in a pack of cards and find all the twos in the pack of cards. Strictly speaking, this estimate is a prospective estimate, “how long will it take to do this in future?â€

Once they have estimated how long each task will take someone is appointed product owner and they have to plan the tasks to be done (with the team).

What I do not tell the teams is that I’m timing them at this stage. I let the teams take as long as they like to get ready: estimate and plan. But I time how long the estimation takes and how long the following planning takes.

Once all the teams are “ready†I ask the teams: “how long did that take?â€

At this point I am asking for a retrospective estimate: how long did it take. The teams have perfect estimation conditions: they have just done it, no time has elapsed and no events have intervened.

Typically they answer are 5 or 6 minutes, maybe less, maybe more. Occasionally someone gets the right number and they are then frequently dismissed by their colleagues.

Although I’ve been running this exercise for nearly 10 years, and have been timing teams for about half that time I’ve only been recording the data the last couple of years. Still it comes from over 65 teams and is consistent.

The total time to get ready to do 2 minutes of work is close to 13 minutes – the fastest team took just 5.75 minutes but the slowest took a whopping 21.25.

The average time spent estimating the tasks is 7 minutes. The fastest team took 2.75 minutes and the slowest 14 minutes.

The average time planning once all tasks are estimated is just short of 6 minutes. One team took a further 13.5 minutes to plan after estimates while another took just 16 seconds. While I assume they had pretty much planned while estimating it is also interesting to note that that team contained several people who had done the exercise a few years before.

(For statistics nuts the mean and median are pretty close together and I don’t think the mode makes much sense in this scenario.)

So what conclusions can we draw from this data?

1) Teams take longer to estimate than do

Everyone taking part in the exercise has been told – several times – that they are preparing to do a 2 minute iteration. Yet on average teams spend 12.75 minutes preparing – estimating and planning – to do 2 minutes of work!

Or to put it another way: teams typically spend six times longer to plan work than to do work.

The slowest team ever took over 10 times longer to plan than to do.

In the years I’ve been running this exercise no team has ever done a complete dry run. They sometimes do little exercises and time themselves but even teams which do this spend a lot of time planning.

This has parallels in real life too: many participants tell me their organization spend a long time debating what should be done, planning and only belatedly executing. One company I met had a project that had been in planning for five years.

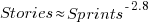

2) Larger teams take longer to estimate than small teams

My second graph shows there is a clear correlation between team size and the time it takes to estimate and plan. I think this is no surprise, one would expect this. In fact, this is another piece of evidence supporting Diseconomies of Scale: the bigger the team the longer it will take to get ready.

This is one reason why some people prefer to have an “expert†make the estimate – it saves the time of other people. However this itself is a problem for several reasons.

Anyone who has read my notes on estimation research (and the later more notes on estimation research) may remember that research shows that those with expert knowledge or in a position of authority underestimate by more than those who do the work. So having an expert estimate isn’t a cure.

But, those same notes include research that shows that people are better at estimating time for other people than they are at estimating time for themselves, so maybe this isn’t all bad.

However, this approach just isn’t fair. Especially when someone is expected to work within an estimate. One might also argue that it is not en effective use of time because the first person – the estimator – has to understand the task in sufficient detail to estimate it but rather than reuse this learning the task is then given to someone else who has to learn it all over again.

3) Post estimation planning is pretty constant

This graph shows the planning delta, that is: after the estimates are finished how long does it take teams to plan the work?

It turns out that the amount time it takes to estimate the task has little bearing on how long the subsequent planning takes. So whether you estimate fast or slow on average it will take six more minutes to plan the work.

Perhaps this isn’t that surprising.

(If I’ve told you about this data in person I might have said something different here. In preparing the data for this blog I found an error in my Excel graphs which I can only attribute to a bug in Excel’s scatter chart algorithm.)

4) Vierordt’s Law holds

People underestimate longer periods of time (typically anything over 10 minutes), and overestimate short period of time (typically things less than two minutes).

Not only do trainees consistently underestimate how long it has taken them to get ready – which is over 10 minutes – but teams which record how long it takes to actually do each task find that their estimates are much higher than the actual time it takes. Even when teams don’t time themselves observation shows that they do the work far faster than they thought they would.

5) Less planning makes more money

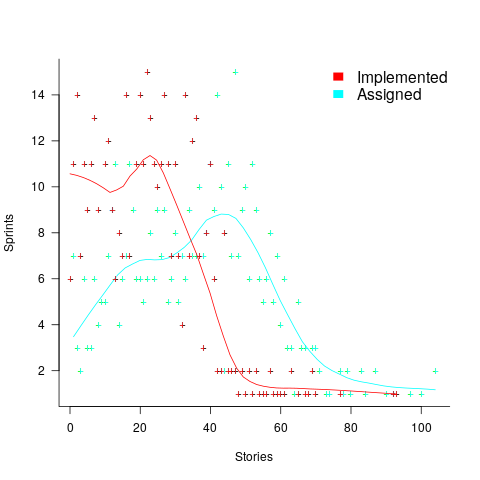

One of my extensions to the original game is to introduce money: teams have to deliver value, measured in money. This graph shows teams which spend less time planning go on to make more money.

I can’t be as sure about this last finding as the earlier ones because I’ve not been recording this data for so long. To complicate matters a lot happens between the initial planning and the final money making, I introduce some money and teams get to plan for subsequent iterations.

Still, there are lessons here.

The first lesson is simply this: more planning does not lead to more money.

That is pretty significant in its own right but there is still the question: why do teams which spend less time planning make more money?

I have two possible explanations.

I normally play three rounds of the game. When time is tight I sometimes stop the game after two rounds. In general teams usually score more money in each successive round. Therefore, teams who spend longer in planning are less likely to get to the third round so their score comes from the second round. If they had time to play a third round they would probably score higher than in round two.

This has a parallel in real life: if extra planning time delays the date a product enters the market it is likely to make less money. Delivering something smaller sooner is worth more.

This perfectly demonstrates that doing creates more learning than planning: teams learn more (and therefore increase their score) from spending 2 minutes doing than spending an extra 2 minutes planning.

The second possible explanation is that the more planning a team does the more difficult they might find it to rethink and change the way they are working.

The $1,600 shown was recorded by a Dutch team this year but the record is held by a team in Australia who scored over $2,000: to break into these high scores teams need to reinterpret the rules of the game.

One of the points of the game is to learn by doing. I suspect that teams who spend longer in planning find it harder to break away from their original interpretation of the rules. How can you think outside the box when you’ve spent a lot of time thinking about the box?

In one training session in Brisbane last year the teams weren’t making the breakthrough to the big money. Although I’d dropped hints of how to do this nobody had made the connection so I said: “You know, a team in Perth once scored over $2,000.†That caused one of the players to rethink his approach and score $1,141.

I’ve since repeated the quote and discovered that simply telling people that such high scores are possible causes them to discover how to score higher.

* * *

I’m sure there is more I could read into all this data and I will carry on collecting the data. Although now I have two problems…

First, having shared this data I might find people coming on my agile software training who change their behaviour because they have read this far.

Second: I need more teams to do this to gather data! If you would like to do this exercise – either as part of a full agile training course or as a stand alone exercise – please call (+44 20 3286 4292) or mail me, contact@allankelly.net, my rates are quite reasonable!

Want to receive these posts by e-mail? – join the newsletter today and receive a free eBook: Xanpan: Team Centric Agile Software Development

The post Estimation, planning, teams and money, some data appeared first on Allan Kelly Associates.

(code+data):

(code+data):